Theoretical Basis and Opportunities for Structural Design: Structural Strategy

Log in to Modern Construction Online for project case study

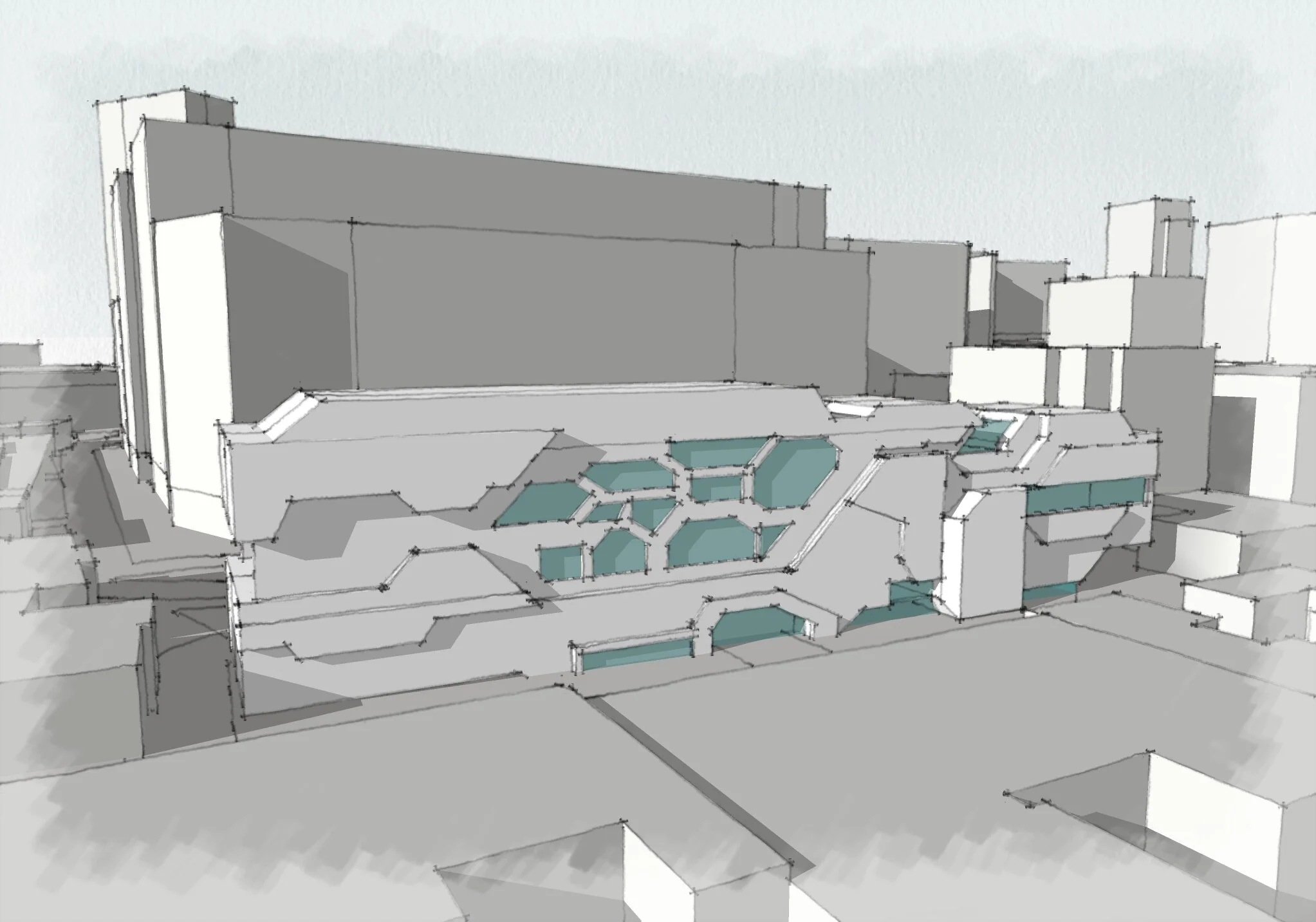

The structural strategy for this high school responds to the need for programmatic diversity and environmental adaptability within a complex architectural brief. Rather than adopting a uniform structural grid that is selectively modified to create variation, the building's structure is composed of interlocking systems—each tailored to its spatial, acoustic, and environmental function. This approach results in a composite structural system that is materially and formally differentiated, with concrete and steel components juxtaposed, rather than integrated, in order to maintain clarity of load paths and reduce structural interdependence.

Mixed-Material Structural Logic

At the core of the structural concept is the use of reinforced concrete and structural steel in tandem, forming a hybrid tectonic composition. Steel’s flexibility and spanning ability suit open-plan areas, double-height volumes, and raked seating in lecture spaces, while concrete provides mass, thermal stability, and load-bearing capacity for cellular teaching spaces, acoustic isolation, and vertical load transmission (Allen & Iano, 2017; Engel, 2007). This hybridization allows the building to act as a series of interlocked volumes—or “modules”—each structurally and environmentally autonomous, yet spatially and functionally interconnected. The separation of these modules by movement joints not only mitigates differential movement between steel and concrete systems but also provides opportunities for thermal and acoustic zoning (Addington & Schodek, 2005). This modular design aligns with performance-based strategies in educational buildings, where different learning environments (lecture halls, workshops, studios, circulation zones) have varied requirements in terms of daylight, thermal response, reverberation time, and occupant density (Dudek, 2000; Szokolay, 2008).

Spatially Derived Structural Morphology

The building’s structural form is derived from the geometry and functional logic of the internal spaces. This results in a structural language that appears ‘moulded’ or shaped by programmatic intent, rather than imposed through repetitive floorplates. Lecture theatres, for example, require raked seating and spatial focus, leading to localized structural solutions such as inclined steel beams or stepped concrete slabs. Adjacent to these, rectilinear teaching blocks with consistent spans use flat slab construction, maximizing material economy and minimizing floor depth. This mirrors Cedric Price’s assertion that "structure should respond to need, not impose form," echoing a shift from static order toward functional responsiveness in educational architecture (Price, 1966). In this case, structural systems are shaped by performance goals—acoustic isolation, vertical hierarchy, visual openness—not simply by cost efficiency or formal regularity.

Structural Options: Comparative Opportunities

Option 1 utilizes a standard flat slab and column system, providing a consistent rectilinear framework. It offers high repetition, ease of construction, and short spans that suit most general classroom functions. Structurally, this option simplifies detailing, enhances buildability, and supports flexible partitioning (Ching & Adams, 2014). The small projecting slab requires local rotation of the structural grid—an opportunity for expressive cantilevered detailing or facade modulation.

Option 2 is a variation of Option 1 with cut-away sections that respond to spatial or daylighting needs. Despite being rectilinear in slab design, the sectional profile enables localized adaptations, allowing the building to respond to environmental drivers such as solar orientation, shading, and views (Givoni, 1998). Structurally, this option requires careful resolution of torsional loads and slab continuity at cut-outs, but provides opportunities for facade articulation and natural ventilation strategies.

Option 3 introduces a double column grid at the edges, supporting long-span prestressed floor slabs across the building’s interior. This allows for wide, uninterrupted teaching spaces and provides structural framing for the circulation corridors. The dual-row column system acts as a visual and functional boundary, creating an intermediate scale between the individual classroom and the campus as a whole. This approach reflects Frampton’s notion of tectonic duality—where structure participates in both spatial definition and symbolic expression (Frampton, 1995). The moulded concrete perimeter in Option 3 enables precast or in-situ construction depending on logistics and budget. Precast concrete offers faster assembly and tighter tolerances, while in-situ casting supports complex geometries and integration with services or façade finishes (Bachmann, 2003). The ability to modulate this edge condition presents an opportunity to express internal functions externally, reinforcing legibility.

Integration of Environmental and Circulatory Structures

Environmental strategy is embedded in the structural design through the use of side-attached ‘backpacks’—shear wall structures housing environmental control systems, staircases, and winter gardens. These backpacks act as lateral stability systems, as well as climatic buffers, mediating between interior learning spaces and the external environment. In temperate climates, this layered approach supports seasonal adaptability, improving insulation in winter while providing passive ventilation in summer (Szokolay, 2008). The use of winter gardens on the short elevations further enhances environmental performance and spatial experience. These vertically stacked glazed spaces act as both thermal buffers and social spaces, offering controlled outdoor environments that bridge indoor teaching zones with the campus landscape. Structurally, these spaces demand attention to thermal expansion joints, condensation control, and lightweight cladding, potentially using steel or aluminium framing systems with integrated shading. The positioning of stairs within service cores, located externally, enables uninterrupted slab spans internally while providing dedicated vertical circulation that aligns with fire compartmentation strategies and facilitates access control. These vertical elements also serve as tectonic markers, reinforcing spatial orientation and symbolic thresholds within the school.

Modular Vertical Stacking: The Tower Concept

The five-module vertical tower, described as a series of stacked programmatic zones, draws from the precedent of historic academic buildings, where a sequence of linked volumes defines the movement and hierarchy of space (Kolarevic, 2005). Each module is structurally distinct but vertically integrated, supporting the idea of spatial continuity across levels—both visually and physically. In this stacked model, structure enables the formation of clear spatial narratives: large-span spaces (e.g., lecture theatres or studios) are interlocked with smaller-scale rooms (e.g., seminar spaces or reading zones), with structure used to articulate transitions. The articulation of walls, doors, and frames enables a legible tectonic order, where load-bearing elements coincide with spatial thresholds and openings, reinforcing the didactic role of structure in the architectural expression of the school.

Overview

The structural strategy of this high school is not a neutral framework but a co-architectural agent—shaping space, enabling environmental performance, and enhancing pedagogical legibility. Through the use of mixed-material systems, modular articulation, and spatially responsive structuring, the design demonstrates a sophisticated tectonic strategy that balances technical performance with expressive architectural intent. The building becomes a case study in performative structure, where structure is deployed not only to span, support, or resist, but to communicate, differentiate, and connect—making it a highly instructive precedent for educational buildings in temperate climates.

References

Addington, D.M. & Schodek, D.L., 2005. Smart Materials and New Technologies: For the Architecture and Design Professions. Oxford: Architectural Press.

Allen, E. & Iano, J., 2017. Fundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and Methods. 6th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Bachmann, H., 2003. Precast Concrete Structures. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Ching, F.D.K. & Adams, C., 2014. Building Construction Illustrated. 5th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Dudek, M., 2000. Architecture of Schools: The New Learning Environments. Oxford: Architectural Press.

Engel, H., 2007. Structure Systems. 3rd ed. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

Frampton, K., 1995. Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Givoni, B., 1998. Climate Considerations in Building and Urban Design. New York: Wiley.

Kolarevic, B., 2005. Performative Architecture: Beyond Instrumentality. New York: Routledge.

Price, C., 1966. Fun Palace Project. London: Cedric Price Archive, Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Szokolay, S.V., 2008. Introduction to Architectural Science: The Basis of Sustainable Design. Oxford: Architectural Press.